by Donna DesRoches

Recently I have had the pleasure of working with groups of students using the iPads and an app called ComicLife. I watched their enthusiasm and excitement while first creating their story, mapping out a short storyboard and then creating the comic.

enthusiasm and excitement while first creating their story, mapping out a short storyboard and then creating the comic.

In the article, Using Student Generated Comic Books in the Classroom, the author believes that because kids are familiar and comfortable with comic books several benefits emerge when they create their own comics particularly in the areas of reading, writing and research skills.

Designing a comic book provides an opportunity for students to be creative in the presentation of their writing. It also allows them to apply and demonstrate their knowledge in an innovative and imaginative way:

- Through comics students can investigate the use of dialogue, succinct and dramatic vocabulary and nonverbal communication.

- Designing comic books can generate expository composition including historical and biographical writing

- The creative process allows students to determine what is most important from their reading, to rephrase it succinctly, and then to organize it logically.

There is a natural fit for creating comics and using the app ComicLife within the grade 9 ELA curriculum but it can be used as a form of summative assessment across all subject areas. The article, Using Comic Life at Every Level of Bloom’s, provides some very specific examples of how the ComicLife App can be integrated into a variety of subject areas including math.

Quality projects using ComicLife occur when students are well prepared both in content knowledge and provided with a clearly designed process.

Some basic steps enable students to use ComicLife to its full advantage:

- Provide a number of comics or graphic novels to students and have them analyze them for comic book elements:

- Flow of images through panels or frames

- Borders and gutters

- Captions (voice of the narrator)

- Speech and thought balloons or bubbles

- Tone shown through shape, bold or italics

- Use of symbols to represent concepts or ideas

- Sound effects represented by words

- Provide students with time to play with and explore the ComicLife app

- Select templates

- Menu buttons to select and change

- Font styles

- Page layouts

- Insert and delete pages

- Sharing options

- Access the camera

- Access the photo gallery

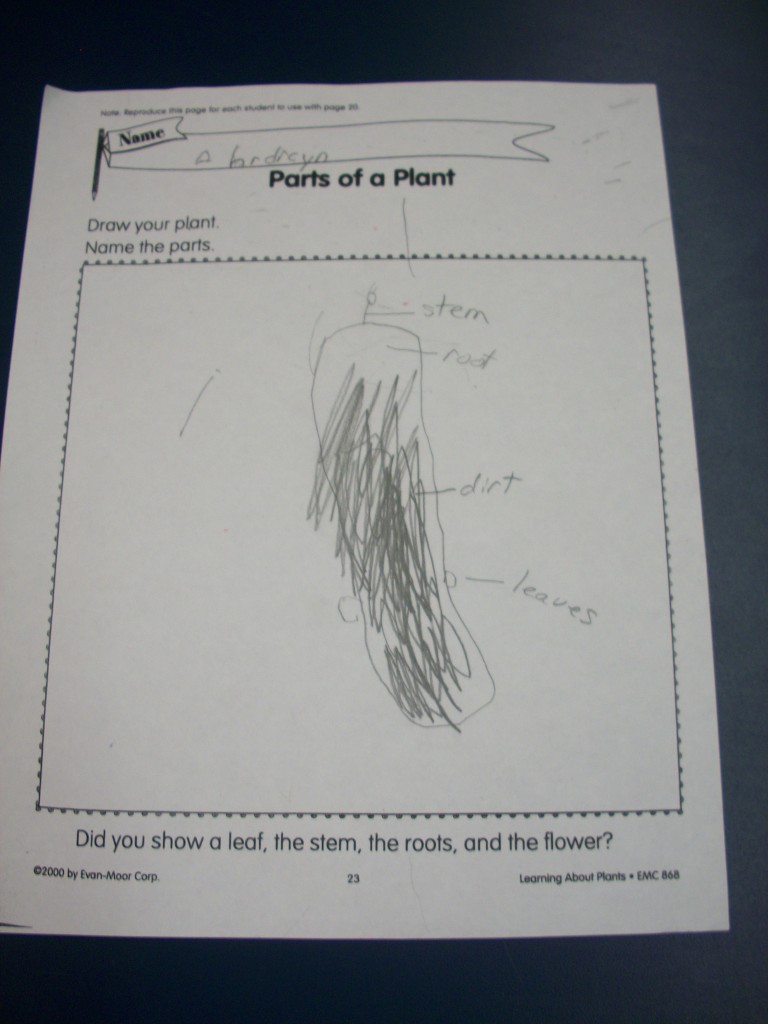

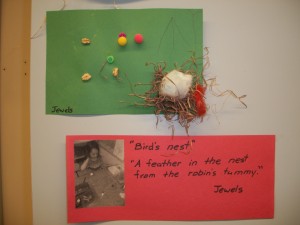

- Provide students with a template or process for creating a rough draft or storyboard of the comic. I usually have students draw panels on a blank sheet of paper. Another way to storyboard is the use of cards as illustrated in this post. Students can then manipulate the sequence of the cards to create the best story flow. Often they need to be encouraged to keep their drawings simple – stick figures are best – and to focus on the dialogue. They should also know that once they begin creating their comic some points in the storyboard will and should change.

- Once students have completed their storyboard they can begin to create their comic. I am always surprised at how important the storyboard is to students as they refer to it often in the midst of the creative process.

- The finished comics can be printed. They can also be shared with their classmates via an Apple TV.