by Michelle Sanderson -First Nations Me’tis Achievement Consultant

What is it that engages families? Especially, in regards to my position, for First Nation families? I think about this question as I prepare for a PD drop-in for the early learning consultant’s workshop. She’s working with 21 new teachers and EA’s and has asked me to speak on one of the four pillars of early learning, engaging FNM families. There’s no easy answer, as the causes of disengagement are complex and multi-faceted. (She’s alloted me 15 minutes)

Through my research and experience as an anti-racist educator, I realize that because there has been a lack of deep and meaningful education regarding First Nations people, that, many teachers and school staff are coming into the position not having a critical analysis of some of the symptoms of colonialism that we see in some of our families. This is a critical problem of course, but can be minimized by stating that we teach to all children. Whether the achievement gap, or as some call it the education dept, agrees, is quite different. Of course, there are the exceptions, and no group of people have homogeneous qualities. But, what I do know, is that at some point, someone deliberately made a decision to not cover First Nation history in Canada’s education. I’ve heard stories of history majors working in our school division, who knew nothing of the Indian Act or residential school! -(until they took our treaty catalyst teacher training). On a more upbeat path, I’m not the only one to notice this, and actions have been taken provincially to address this problem. Amid the changes recently, is the inclusion of First Nation and Me’tis specific outcomes and indicators Saskatchewan has made mandatory to teach, in all grades from pre-kindergarten to grade 12. As well, the province has made teaching treaty outcomes and indicators mandatory. Since the mid 1990’s, recent graduates from teacher’s colleges, have been compelled by the University of Saskatchewan’s college of education to take anti-racist or Native Studies classes. I’m not sure if these classes are mandatory across Canada, or Saskatchewan for that matter. However I do applaud the University of Saskatchewan’s efforts to treat the roots of this problem and hopefully, we will continue to see growth in this area. On a side note,The University of Manitoba, has made Indigenous Studies classes mandatory in every college. Locally, within our own school division, we have had many events, including, but not all are listed, such as treaty catalyst teacher training and anti-racist/anti-oppressive education to address this education void. These are small efforts, but that’s how change happens. I applaud those teachers for taking the time to get this training in our school division. Along with the many benefits to having this training, is that it can only serve to create more skilled teachers in meeting the province’s outcomes and indicators and to create good relations amongst all people. (ie. interrupt racism) Another initiative from the province in pilot project form, is the “Following their Voices” project. In short, it’s a project, which starts with research by asking teachers and community members, students, parents what they think about education, and where they are, and where they wish it would go. Problems are identified, and actions are taken to address the problems. Again, small pockets of change to address the First Nations Metis achievement gap, or the First Nations Metis education debt, whatever you want to call it. Basically, these trainings are giving educators a much needed critical analysis that is needed to connect in meaningful and humanizing ways with First Nations and Metis students and families.

At one point, I myself, lacked the analysis that was needed to understand the effects of colonialism. A lot of the racism, and stereotypes that were out there, floating in space without a deeper analysis, caused me to internalize the racism at a very young age. One need only turn on the news, or drive down the street to see the effects of colonialism. Sadly,and it’s the negative images that makes the news more often than naught. Stories of strength and resilience, plentiful though they are, are often left to more spectacular negative news items. That in itself is a future project to address. Back to the subject at hand. Because of these internalized racial images I had been exposed to, I had to have my eyes focused another way, from someone else. I had to be shown that I was not a bad person, or that I wasn’t worthy, or that something wasn’t wrong with me, or that my genes weren’t faulty. It’s a process, that as a racialized being, I must continually visit and interrupt within myself each and every day. Being someone who has experienced much trauma due to my race and racism, due to being a child raised in a community of first and second generation residential school survivors, who were themselves, victims of abuse and trauma, guilt and shame, I had to analyze why I had these negative thoughts about myself and my people, the way I did. My healing journey is ongoing.

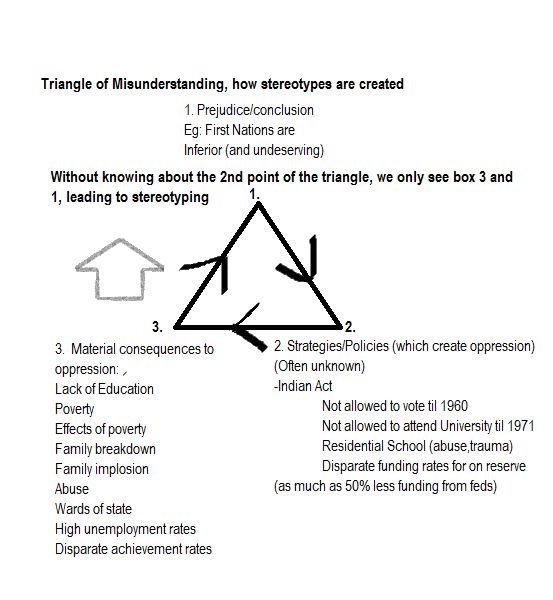

One of the tools which helped me to understand the effects of colonialism, racism and stereotyping, was passed to me by an anti-racist friend and colleague of mine, by the name of Sheelah Mclean. She shared an illustration with me, to help me to understand within minutes of why there were such negative perceptions of First Nations people, and impressed upon me the importance to teach the First Nation Me’tis history education void. This illustration helped me to depersonalize racial stereotypes about myself and my people and to make sense of them. This illustration can also be used to understand multiple types of oppression. The illustration is quite simple. It is in the shape of a triangle. Starting from bottom right, we move clockwise. The first point in the bottom right corner of the triangle represents the policies, procedures and strategies which were put in place to oppress Indian people. The second point of the triangle, bottom left, includes the material consequences of the oppression. We can use this illustration to take apart the stereotypes and the myths and to challenge ourselves as to how we came to conclusions, based on the partial picture we are presented when we process a large group of First Nations people through our education system without knowing our own shared history. At the top of the triangle is the thoughts, inferences, or the conclusions that people come to without understanding that these are the results of the policies and procedures. We can clearly see that the direct result of oppression when we look at this triangle, travelling clockwise. So, if we just see the bottom left, (3.) the results of policy directed at First Nation people, is obscured (2), then we can see how stereotypes are made, and generalizations like, (1.)“Indians are inferior” are created. (Of course, this is just a brief snapshot of some of the strategies/policies unleashed upon Indian people.) Which, is what makes treaty catalyst teacher training and teaching our shared history about residential school, treaties that much more effective in interrupting racism and the creation of stereotypes.

As an educator, I feel that there is an urgency to breaking the stereotypes and myths around First Nations people. It is these negative ideas, about First Nations people which are interrupting good relations across the spectrum. If First Nations are to fully participate in the economy, we need to confront the stereotypes.The full participation of First Nation people in the economy was the intention and was embedded in the spirit of our treaties. It’s important to understand that the First Nations experience as Canadians, as “Indians” as defined by Canada has been disastrous to First Nations people. I think the future will brighten, and the possibilities will expand, when we as Canadians can together come to an understanding, of our shared history. When that happens, we can begin to humanize each other in meaningful ways and engage families and communities who have long been divorced from trusting education. As First Nation families realize that teachers and schools are beginning to come in as allies, engagement will rise. But as well, it will begin a process where non-Native teachers will also be questioning and redefining within themselves, what it means to be white.

Further Reading:

Non Native teachers in Native Communities by John Taylor

/white-settlers-and-indigenous-solidarity-confronting-white-supremacy-answering-decolonial-alliances